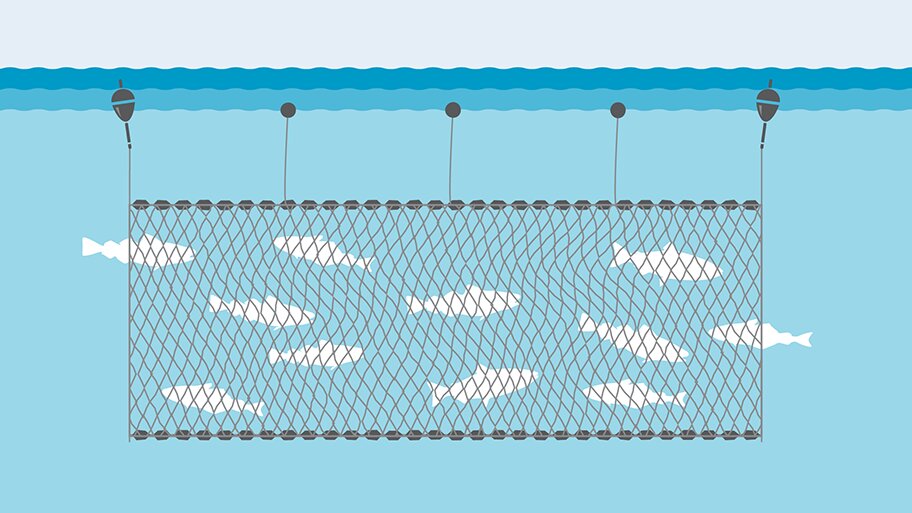

Around the world, fishermen use low-cost nets that sit like fences on coastal sea floors. Known as gill nets, this type of gear is highly effective at catching fish when the mesh snags them by their gills. Unfortunately gill nets also catch a host of other species by mistake such as sardines, sharks along with assorted sea turtles, dolphins, and even whales.

At times these gill nets get overloaded with fish and form a “wall of death”. The nets break free and settle to the bottom. The dead fish in the nets are eaten by scavengers, and then the nets float again – a new wall of death kilometres long, unconnected to a fishing ship and causing irreparable damage.

Used for hundreds of years, the use of gill nets became particularly damaging with the advent of the first powered drums to haul in nets, and the use of synthetic material to make nets in the 1960s.

Gill nets can be made more selective to catch fish of a particular species and size and avoid undesired fish. This can be done by regulating mesh sizes and net strengths. Adding acoustic pingers to gill nets reduce the incidence of dolphins caught in the nets by over 90%.

California has banned gill net fishing in near-coastal waters, and other states are starting to regulate this type of fishing by limiting the fishing seasons and/or the type of nets used.

Belize, a country for which marine fishes are a major touristic asset has completely banned the use of gill nets and fishers’ compensation to surrender their gear. While a gill net ban is a huge victory for Belize, this deadly gear is still in use in many other parts of the world.

Very deep driftnets that had lengths of tens of kilometres were for decades commonly deployed in the high seas to catch tuna beyond the jurisdictions of coastal countries. They were outlawed by the United Nations in 1989 because of the damage they inflicted, but they continue to be used widely, though illegally. They are most often used to catch swordfish, tuna, and salmon.

By outlawing giant driftnets United Nations have shown that it is possible to reverse course and protect marine diversity rather than mindlessly destroy it. There is a long road ahead, but a start has been made.