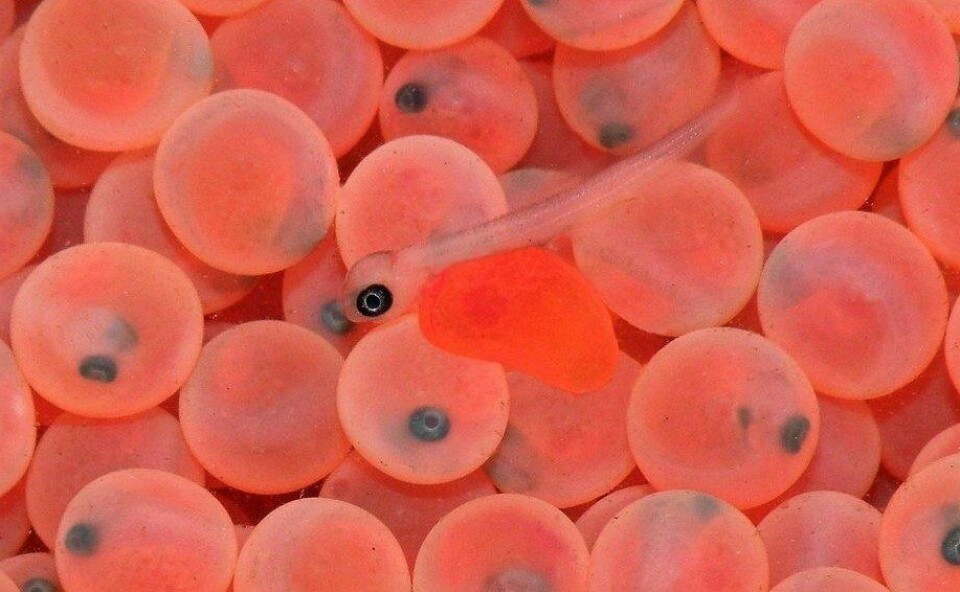

Many aquatic animals, including certain species of fish, prawns, and crabs, undertake remarkable migrations into the ocean to spawn. This behaviour, while energetically costly and sometimes dangerous, has evolved because it significantly increases the survival chances of their offspring. The movement from freshwater or coastal habitats into open ocean spawning grounds is driven by a combination of ecological, evolutionary, and physiological factors.

One primary reason for oceanic spawning is access to favourable environmental conditions for eggs and larvae. The open ocean often offers stable temperatures, higher oxygen levels, and nutrient-rich waters that promote plankton growth. Since plankton forms the base of the food chain for many marine larvae, spawning in these areas increases the likelihood that the young will find sufficient food during their critical early stages of development.

Another key factor is reduced predation pressure. While it may seem counterintuitive, spawning in the vastness of the ocean can actually dilute the density of eggs and larvae, making it harder for predators to consume a significant portion. In contrast, staying in shallow or enclosed waters might concentrate offspring in a smaller area, making them easy targets.

For many species, ocean currents also play a strategic role. By releasing eggs or larvae into specific currents, animals can ensure their young are transported to suitable nursery habitats, such as estuaries or mangrove forests. This method of passive dispersal increases the geographic range and survival odds of the next generation.

In some species, like certain prawns and crabs, the adults live much of their lives in estuaries or nearshore environments but must return to full-salinity ocean waters to successfully reproduce. This is because reproductive physiology, such as proper egg development and larval hatching, often requires conditions only found offshore.

The migration of fish, prawns, and crabs into the ocean to spawn is an adaptive behavior shaped by natural selection. By seeking out optimal conditions for reproduction, these species increase the likelihood that their offspring will survive, grow, and continue the life cycle—a timeless journey driven by the need to ensure the future.