Whales and dolphins are remarkable. But why are they so important? What is so special about whales and dolphins? Whales play an amazing role in an ecosystem that keeps every creature on Earth alive, including you.

Humans have done enormous damage to the planet including killing millions of whales and wiping out up to 90% of some populations. Yet few people, let alone governments, are aware that recovering whale populations can help fight the damage we cause.

How whales support the marine ecosystem:

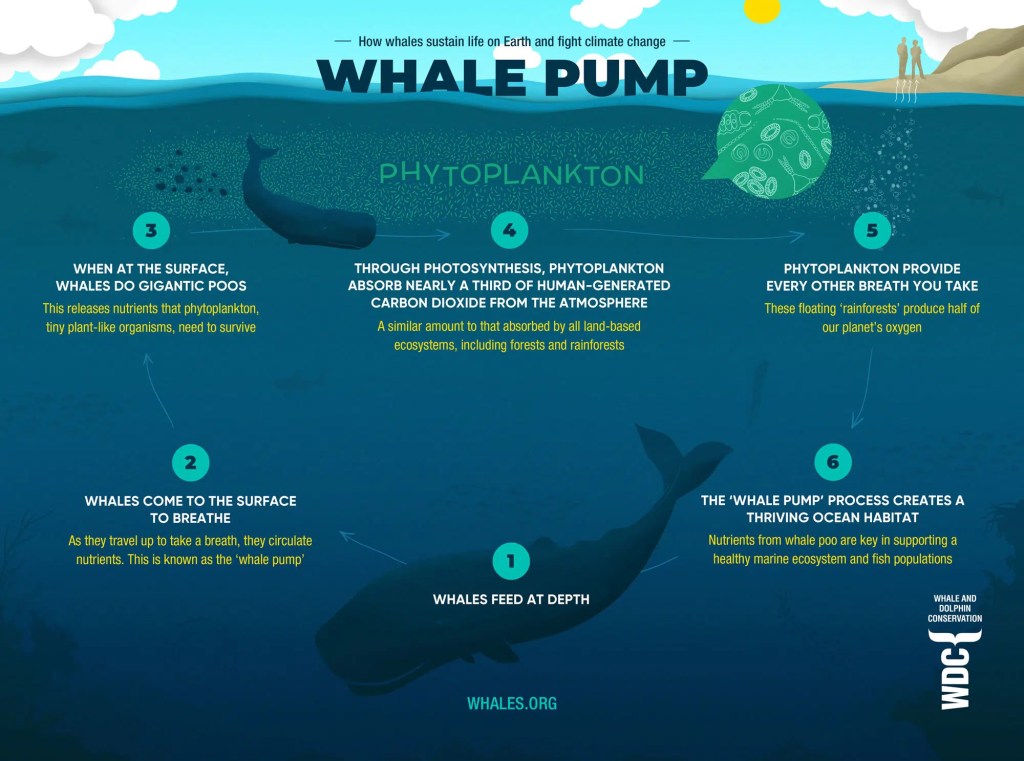

Whales re-distribute nutrients across the seas; essential to the marine eco-system, and the production of phytoplankton, which produces over half of the world’s oxygen. This is known as the “Whale Pump”.

Different species of whales feed on a range of marine creatures, including krill and fish, in the dark depths of the world’s oceans.

Whales then come up near the surface to poo – and when whales poo, they really poo. Whale poo is a brilliant fertiliser for microscopic plants called phytoplankton. More whale poo means more phytoplankton. Phytoplankton absorbs carbon from the atmosphere – millions of tonnes of it.

Carbon in the atmosphere is a significant cause of climate change. Climate change is the greatest threat to all life on Earth.

So, the more whales there are, the more phytoplankton there is, and the more carbon is taken out of the atmosphere.

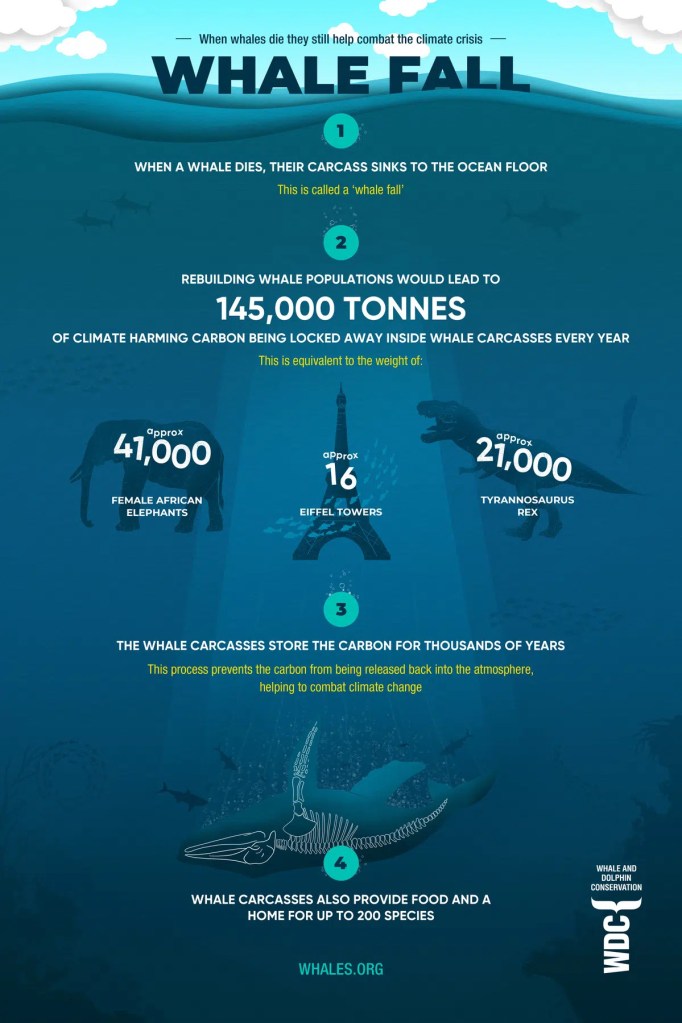

Even in death, whales sustain life. When whales die, they sink to the seabed, where they become mini-ecosystems sustaining all manner of marine life, taking huge amounts of carbon with them to the seabed. Researchers estimate that because of whaling, large whales now store approximately nine million tonnes lesscarbon than before large-scale whaling.

Planet Earth needs a healthy ocean. And a healthy ocean needs whales. It isn’t enough to conserve species, populations, and individuals. We need to restore their ocean environment and allow populations to recover to levels that existed before industrial scale whaling and fishing devastated the oceans.