Fish are typically associated with swimming, gliding effortlessly through water. However, some species of fish exhibit a fascinating behaviour: jumping out of the water. This behaviour, while surprising to many, serves a variety of purposes crucial for the survival and success of these fish. Understanding why certain fish jump requires an exploration of their ecological needs, predator-prey dynamics, and reproductive strategies.

Escaping Predators

One of the most common reasons fish jump is to escape predators. In the wild, many fish are pursued by larger predators, both aquatic and aerial, and jumping out of the water can serve as an effective escape mechanism. By leaping into the air, fish can confuse or evade their pursuers, disrupting the predator’s attack pattern. For instance, mullet, a species known for its acrobatic jumps, often leaps out of the water when chased by larger fish. The sudden change in direction and environment can give the prey a crucial moment to escape.

Catching Prey

In some cases, fish jump to catch prey. This behaviour is particularly observed in species that feed on insects or other small creatures found near or on the water’s surface. For example, archerfish are known for their ability to spit jets of water to knock insects into the water, but they may also leap out of the water to capture prey that is otherwise out of reach. Similarly, some species of dolphins have been observed using jumping to herd fish into tight groups, making them easier to catch.

Reproductive Behaviour

Jumping can also play a role in the reproductive behaviour of certain fish species. During spawning season, fish such as salmon are famous for their leaps as they navigate upstream to reach their breeding grounds. These jumps are necessary for overcoming obstacles like waterfalls and rapids, allowing them to reach the calm waters where they lay their eggs. The ability to jump is crucial for the completion of their life cycle, ensuring that they can reproduce successfully in the most suitable environments.

Navigating Obstacles

For many fish, jumping is a practical way to navigate obstacles in their environment. In addition to the spawning-related jumps of salmon, many other fish species leap to avoid physical barriers or to move from one body of water to another. This is particularly important in areas where water levels fluctuate, and fish need to move quickly to find suitable habitats. The mangrove killifish, for instance, is known to leap from one tide pool to another, especially when the pools begin to dry up.

Communication and Social Interaction

In some species, jumping may serve as a form of communication or social interaction. Fish such as dolphins, though not fish in the strict biological sense, engage in complex behaviours that include jumping as part of their social dynamics. These jumps can be a way to signal other members of the group, establish dominance, or even play. While the exact reasons for these jumps can vary, they often involve more than just a physical need, encompassing social and environmental cues.

Environmental Responses

Finally, some fish jump as a response to changes in their environment. This can include sudden changes in water quality, such as low oxygen levels, where jumping might temporarily allow them to access more oxygen-rich water near the surface. This behaviour is sometimes observed in fish kept in aquariums that lack adequate aeration, where the fish leap in an apparent attempt to reach better conditions.

Fish jumping is a multifaceted behaviour that serves a variety of functions essential to the survival and reproduction of different species. Whether escaping predators, catching prey, navigating obstacles, or communicating with others, jumping is a vital adaptation that allows fish to thrive in diverse and often challenging environments. Understanding why certain fish jump enriches our knowledge of aquatic life and highlights the remarkable strategies these creatures employ to survive and succeed in their natural habitats.

The Life Cycle of the Swimming Prawn

The swimming prawn, a vital species in marine ecosystems and a valuable resource in the global seafood industry, has a fascinating and complex life cycle that reflects its adaptability and resilience. Like many marine crustaceans, swimming prawns undergo multiple stages of development, each characterized by distinct physical and behavioural changes. Understanding this life cycle is crucial for sustainable management and conservation efforts, as well as for optimizing aquaculture practices.

Egg Stage

The life cycle of the swimming prawn begins with the female laying eggs, typically in offshore waters. Fertilization is usually external, occurring when the female releases her eggs into the water, where they are fertilized by the male’s sperm. The eggs are often carried by the female, attached to her swimmerets (appendages on the underside of the abdomen), where they remain until they are ready to hatch. The duration of the egg stage can vary depending on environmental conditions such as temperature and salinity, but it generally lasts for several days to a few weeks.

Larval Stage

After hatching, the prawn enters the larval stage, which is characterized by several successive molts. During this stage, the larvae are planktonic, meaning they drift with the ocean currents, which can transport them over long distances. The larval stage is divided into several sub-stages, including nauplius, protozoea, and mysis stages, each marked by specific morphological changes. For example, in the nauplius stage, the larvae are tiny and have only basic appendages, while in the mysis stage, they begin to resemble adult prawns more closely, with the development of more complex structures like antennae and a segmented body.

The larval stage is a critical period for swimming prawns, as they are highly vulnerable to predation and environmental fluctuations. Their survival during this stage depends largely on the availability of suitable food sources, such as plankton, and the presence of favourable ocean currents that can carry them to safer, nutrient-rich waters.

Post-Larval and Juvenile Stage

Once the larvae have undergone several molts and reached a more developed form, they enter the post-larval stage. At this point, they begin to settle from the planktonic phase to the benthic environment, where they live on or near the ocean floor. The post-larvae are more robust and capable of active swimming, which allows them to seek out suitable habitats, such as estuaries or coastal areas with abundant vegetation, where they can find food and shelter.

As they grow, the prawns continue to molt, shedding their exoskeletons to accommodate their increasing size. This molting process is essential for their development, as it allows them to grow and develop the complex body structures required for adult life. During the juvenile stage, the prawns begin to display behaviours typical of adult prawns, such as burrowing into the substrate and becoming more adept at avoiding predators.

Adult Stage

The prawn reaches maturity in the adult stage, typically within a few months to a year, depending on species and environmental conditions. Adult swimming prawns are fully developed with a segmented body, long antennae, and strong swimming legs that allow them to navigate their environment effectively. They are omnivorous, feeding on a variety of plant and animal matter, including detritus, small fish, and algae.

Reproduction in adult prawns involves complex mating behaviours, often linked to environmental cues such as temperature and the lunar cycle. Once mating occurs, the life cycle begins anew with the female laying eggs, perpetuating the species.

The life cycle of the swimming prawn is a remarkable journey of transformation, adaptation, and survival. From the vulnerable larval stages to the resourceful and mobile adult phase, each stage of development is crucial for the prawn’s survival and success in its environment. Understanding this life cycle is key to managing prawn populations sustainably, whether in wild fisheries or aquaculture, ensuring that this important species continues to thrive in the world’s oceans.

Why Mission Rocks is Called Mission Rocks

Mission Rocks, a scenic and geologically significant site within the iSimangaliso Wetland Park in South Africa, is known for its rugged coastline, distinctive rock formations, and rich biodiversity. The name “Mission Rocks” carries historical significance, rooted in the region’s colonial past and the activities of Christian missionaries who once operated in the area. Understanding the origin of this name provides insight into the cultural and historical context of the iSimangaliso Wetland Park, adding another layer of depth to the appreciation of this remarkable landscape.

The name “Mission Rocks” is believed to have originated during the 19th century, a period when Christian missionaries were actively involved in establishing missions along the eastern coast of South Africa. These missions aimed to convert the local Zulu population to Christianity and often served as centres for education and social services. The area now known as Mission Rocks was reportedly a location frequented by these missionaries, either as a place of refuge, gathering, or contemplation during their travels along the coast.

The rugged coastline, with its dramatic rock formations and proximity to the ocean, would have provided a serene and reflective environment for the missionaries. The rocks themselves may have served as natural landmarks, guiding the missionaries as they navigated the challenging terrain. Over time, the association between the missionaries and this particular stretch of coast led to the area being referred to as “Mission Rocks.”

Mission Rocks is characterized by its striking rocky outcrops, which are remnants of ancient geological processes. These formations, composed primarily of sandstone, have been shaped by millions of years of erosion and weathering, creating a rugged landscape that contrasts with the surrounding sandy beaches and dense coastal vegetation. The rocks are not only geologically significant but also serve as important habitats for a variety of marine and terrestrial species, making the area ecologically valuable.

The name “Mission Rocks” thus reflects a convergence of natural and human history. While the site is primarily recognized for its natural beauty and geological features, the historical connection to the missionaries adds a cultural dimension that enriches the narrative of the iSimangaliso Wetland Park. It serves as a reminder of the complex interactions between humans and the environment, where cultural history is intertwined with natural landscapes.

Today, Mission Rocks is a popular destination within the iSimangaliso Wetland Park, attracting visitors for its scenic views, rich biodiversity, and opportunities for exploration. The site is particularly noted for its rock pools, which teem with marine life, making it a favorite spot for snorkeling and tide-pooling. The area also offers hiking trails that lead through coastal forests and provide panoramic views of the Indian Ocean.

For many visitors, the name “Mission Rocks” evokes a sense of mystery and historical intrigue, prompting curiosity about the origins of the name and the stories of the people who once frequented the area. The enduring legacy of the missionaries who inspired the name is reflected in the continued use of “Mission Rocks,” serving as a link between the past and present.

Mission Rocks in the iSimangaliso Wetland Park is a site where natural beauty and historical significance converge. The name “Mission Rocks” is a testament to the area’s association with Christian missionaries in the 19th century, who left their mark on the landscape through their presence and activities. This historical connection adds depth to the understanding of the site, making it not only a place of natural wonder but also a location steeped in cultural heritage. As part of the iSimangaliso Wetland Park, Mission Rocks continues to be a place of exploration, reflection, and appreciation for both its natural and historical significance.

Pavement Rock Formations Along the iSimangaliso Coast

The iSimangaliso Wetland Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site located in South Africa, is renowned for its rich biodiversity and stunning landscapes. Among its many natural wonders are the pavement rock formations that line parts of its coastline. These formations, which resemble flat, expansive stone surfaces, are not only visually striking but also geologically significant. They offer insights into the region’s geological history, coastal processes, and the dynamic interactions between land and sea.

Pavement rock formations are primarily composed of sedimentary rocks, such as sandstone and limestone, which have been subjected to extensive weathering and erosion over millions of years. These rocks were originally laid down in horizontal layers, often as sediments in ancient marine environments. Over time, the movement of tectonic plates, changes in sea levels, and the accumulation of sediments led to the creation of vast, flat rock surfaces. The consistent pounding of ocean waves, combined with the chemical action of saltwater, has further eroded and smoothed these rocks, giving them their characteristic flat and expansive appearance.

In the iSimangaliso Wetland Park, these formations are particularly prominent along certain stretches of the coast, where the interplay of geological forces and marine activity has been most intense. The pavement rocks often extend into the intertidal zone, where they are periodically submerged and exposed by the tides. This exposure to the elements continues to shape and refine their surfaces, creating unique patterns and textures.

Beyond their geological interest, the pavement rock formations play a crucial role in the coastal ecosystem of the iSimangaliso Wetland Park. These flat rock surfaces provide a stable substrate for a variety of marine organisms, including barnacles, limpets, and various species of algae. The crevices and pools that form on the rock surfaces during low tide create microhabitats for small marine life, such as crabs, mollusks, and anemones. These organisms form the base of a complex food web that supports larger predators, including fish and birds.

The pavement rocks also act as natural barriers, helping to protect the coastline from the full force of ocean waves. By absorbing and dissipating wave energy, these formations reduce coastal erosion and contribute to the stability of nearby sandy beaches and dunes. This protective function is particularly important in the iSimangaliso Wetland Park, where the preservation of diverse habitats is essential for maintaining the area’s ecological integrity.

In addition to their scientific and ecological importance, the pavement rock formations along the iSimangaliso coast have significant cultural and aesthetic value. For centuries, these rocks have been part of the natural landscape that indigenous communities and early settlers have interacted with. The formations are often viewed as natural landmarks, contributing to the sense of place and identity of the region.

From an aesthetic perspective, the pavement rocks are a major attraction for tourists and nature enthusiasts. Their flat, expansive surfaces, often set against the backdrop of the ocean, create dramatic and picturesque scenes, particularly during sunrise and sunset. The interplay of light and shadow on the textured rock surfaces adds to the visual appeal, making these formations a popular subject for photography and art.

The pavement rock formations along the iSimangaliso coast are a remarkable natural feature that highlights the interplay of geological processes and coastal dynamics. These formations not only offer a window into the region’s geological past but also support a rich and diverse ecosystem. Their cultural and aesthetic significance further enhances their value, making them an integral part of the iSimangaliso Wetland Park’s unique and treasured landscape. As such, they deserve continued protection and appreciation as part of the park’s natural heritage.

Jellyfish Appearing in Certain Wind Conditions

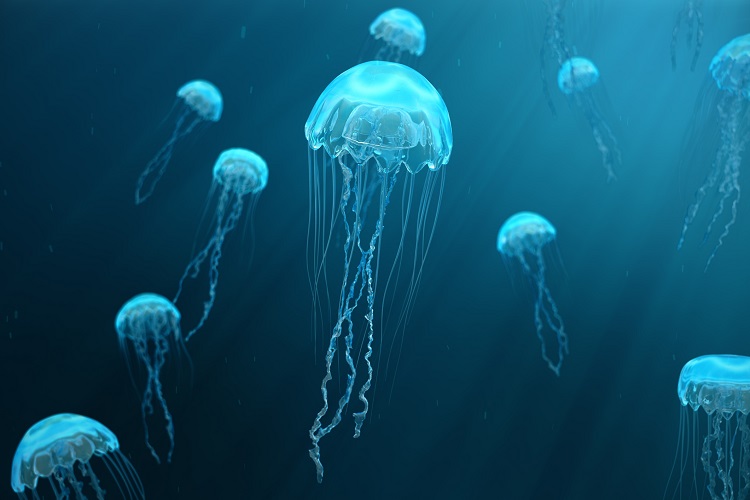

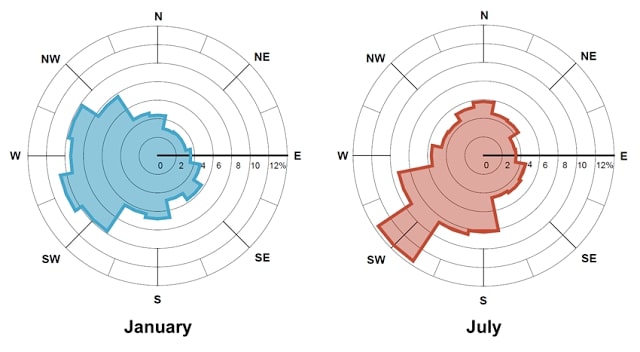

Jellyfish are fascinating marine creatures that are often observed in large numbers along coastlines under specific environmental conditions. Among the factors influencing their appearance, wind patterns play a significant role. The relationship between jellyfish presence and wind conditions can be explained by the passive nature of jellyfish movement, the role of ocean currents, and the way wind influences water surface dynamics. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for predicting jellyfish blooms and managing their impact on coastal activities.

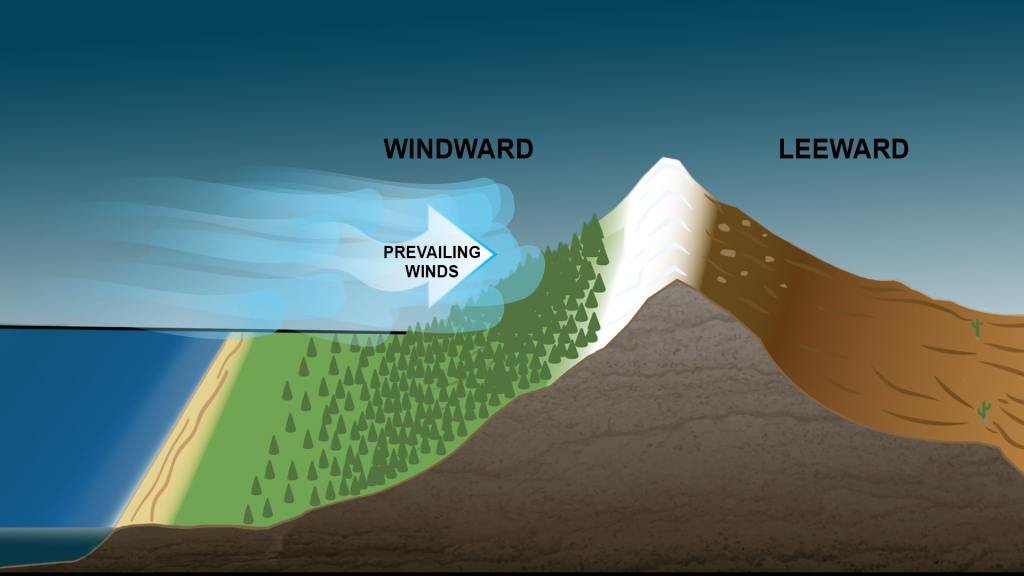

Jellyfish lack strong swimming abilities, relying instead on the currents and tides to carry them through the water. As a result, their distribution is heavily influenced by external forces such as wind. When winds blow consistently from a certain direction, they can create surface currents that push jellyfish toward the shore or into concentrated areas. For example, onshore winds—those blowing from the sea toward the land—can drive surface water, and with it, jellyfish, toward the coastline. This results in the sudden appearance of jellyfish swarms along beaches.

Conversely, offshore winds, which blow from land toward the sea, can have the opposite effect, pushing jellyfish away from the shore and into deeper waters. This dynamic explains why jellyfish might be more or less abundant in certain coastal areas depending on the prevailing wind conditions.

Another wind-related phenomenon that affects jellyfish distribution is Langmuir circulation. This is a process that occurs when steady winds create a series of parallel, rotating water cells on the ocean’s surface. These cells form alternating zones of convergence (where water comes together) and divergence (where water moves apart). Jellyfish, along with other floating objects and organisms, tend to accumulate in the convergence zones. This accumulation can lead to the formation of long lines or patches of jellyfish, which can be seen stretching along the water surface. As these zones of convergence are shaped and moved by the wind, large numbers of jellyfish can be transported toward the shore or concentrated in particular areas.

Wind patterns are also linked to seasonal changes, which can trigger jellyfish blooms—sudden increases in their population. In many regions, the onset of seasonal winds, such as the monsoons or trade winds, coincides with a rise in jellyfish numbers. These winds can enhance upwelling, a process where deep, nutrient-rich water rises to the surface, providing an ideal environment for the growth of plankton. Since jellyfish feed on plankton, an increase in plankton due to upwelling can lead to a corresponding increase in jellyfish populations. As the wind-driven currents move these blooming populations, they may become more noticeable along certain coastlines.

The appearance of jellyfish in certain wind conditions is closely linked to their passive movement and the way wind influences oceanic currents and surface dynamics. Onshore winds can push jellyfish toward the coast, while offshore winds may drive them away. Phenomena like Langmuir circulation further contribute to the accumulation and distribution of jellyfish in specific patterns. Additionally, seasonal wind patterns can indirectly promote jellyfish blooms by enhancing the conditions favourable for their prey. By understanding these relationships, scientists and coastal managers can better predict and respond to jellyfish occurrences, helping to mitigate their impact on tourism, fishing, and coastal ecosystems.

How To Treat A Jellyfish Sting

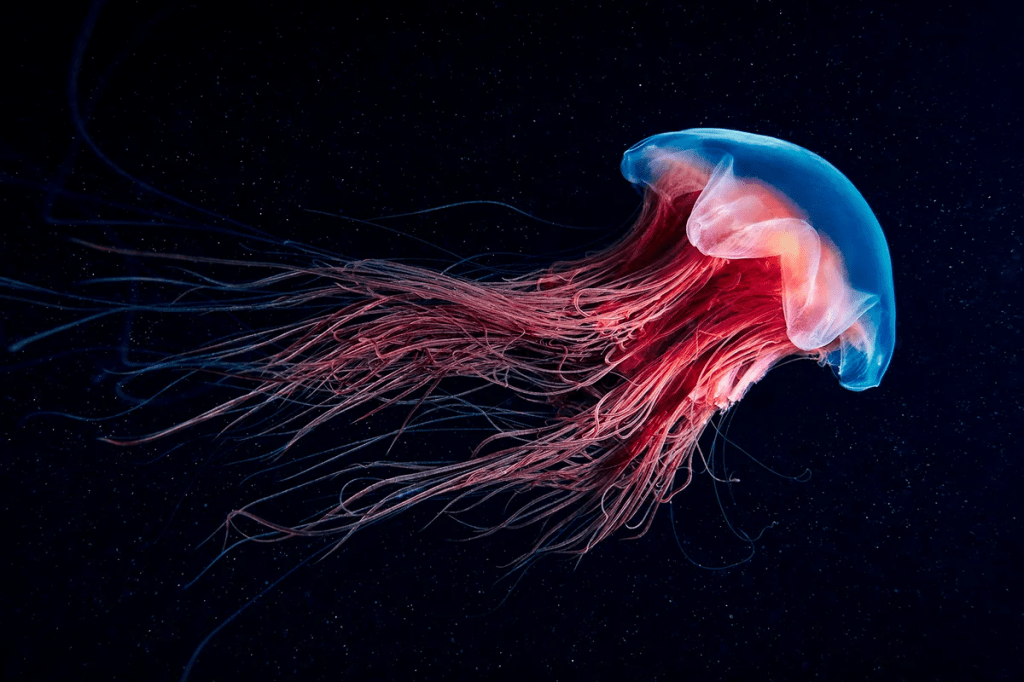

Jellyfish stings are a common hazard in coastal waters, particularly in warm and tropical regions. These stings can range from mildly irritating to potentially life-threatening, depending on the species of jellyfish involved. Proper treatment is crucial to alleviate pain, prevent further envenomation, and reduce the risk of complications. This essay outlines the steps to effectively treat a jellyfish sting and the rationale behind each action.

When a jellyfish sting occurs, the first priority is to ensure the safety of the victim and prevent further stings. If possible, the victim should be moved out of the water to avoid additional contact with jellyfish tentacles. It is important to remain calm, as panic can exacerbate the situation and make treatment more difficult.

The next step is to deactivate the stinging cells, known as nematocysts, that may still be embedded in the skin. Rinsing the affected area with vinegar (acetic acid) is widely recommended, as it can neutralize the nematocysts and prevent them from releasing more venom. If vinegar is not available, saltwater can be used as an alternative, though it is less effective. Freshwater should be avoided, as it can cause the nematocysts to release more venom, worsening the sting.

After rinsing, it is important to carefully remove any visible jellyfish tentacles from the skin. This should be done using a pair of tweezers or the edge of a flat object, such as a credit card, to gently scrape the tentacles off. Direct contact with the tentacles should be avoided, as they can still sting even after being detached from the jellyfish.

Once the tentacles are removed, the affected area should be soaked in hot water, if possible. The water should be as hot as the person can tolerate (but not scalding) and should be applied for about 20 to 45 minutes. Heat can help reduce pain by inactivating the toxins in the venom.

Pain from a jellyfish sting can be intense, and over-the-counter pain relievers such as ibuprofen or acetaminophen can help manage discomfort. Additionally, applying a cold pack to the affected area after the initial hot water treatment can reduce swelling and numb the pain.

In some cases, particularly when stung by more dangerous species like box jellyfish, Portuguese man o’ war, or Irukandji jellyfish, the victim may experience severe symptoms such as difficulty breathing, chest pain, or anaphylactic shock. These symptoms require immediate medical attention. In such situations, emergency services should be contacted, and the victim should be monitored closely until help arrives.

For individuals who experience systemic symptoms, such as nausea, dizziness, or muscle spasms, or if the sting covers a large area of the body, seeking medical attention is advised even if the initial symptoms seem mild. Medical professionals can provide treatments such as antihistamines, corticosteroids, or antivenom, depending on the severity of the sting.

Preventing jellyfish stings is the best approach to avoiding the associated pain and complications. Swimmers should be aware of local jellyfish warnings and avoid swimming in areas where jellyfish are known to be present. Wearing protective clothing, such as a full-body swimsuit or a wetsuit, can also reduce the risk of stings.

Treating a jellyfish sting involves a series of careful steps to minimize pain, neutralize venom, and prevent further injury. Immediate first aid, including rinsing with vinegar, removing tentacles, and managing pain, is essential. In severe cases, prompt medical attention can be lifesaving. By understanding how to treat jellyfish stings effectively, individuals can better protect themselves and others from the dangers of these marine creatures.

The Different Shapes of Game Fish and their Purpose

Game fish, sought after by anglers for sport and recreation, exhibit a fascinating variety of shapes that are closely tied to their survival strategies, feeding habits, and ecological roles. The shape of a fish’s body is not just a random trait but a highly specialized adaptation that allows it to thrive in its environment. Understanding the different shapes of game fish and their purposes offers insights into how these species have evolved to become the proficient predators and agile swimmers they are today.

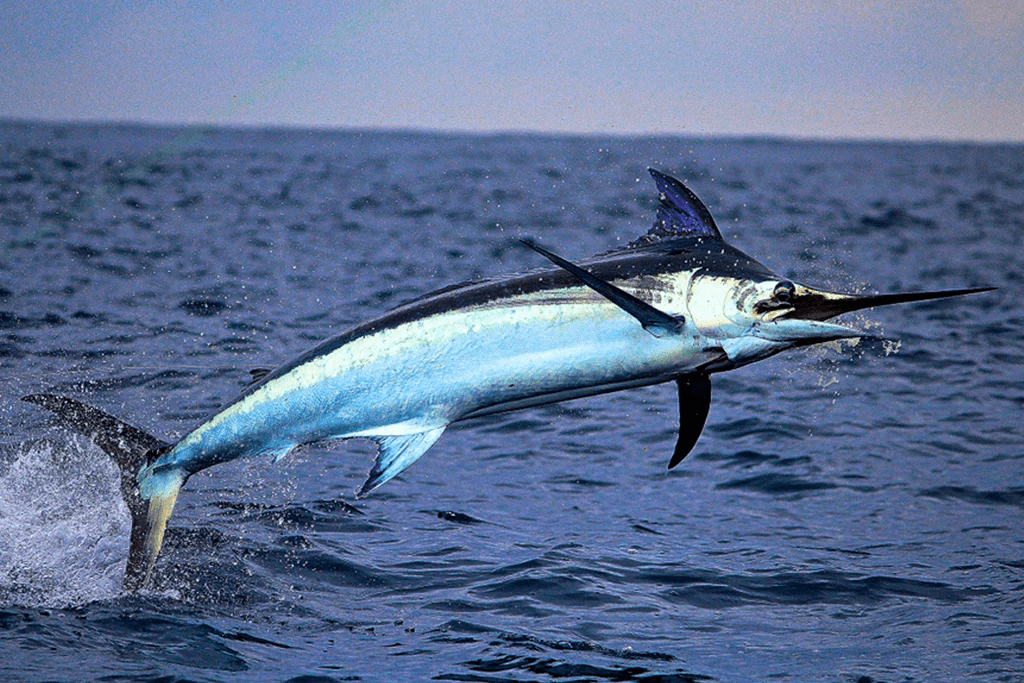

One of the most common shapes among game fish is the streamlined, torpedo-like body, seen in species such as tuna, marlin, and barracuda. This shape is designed for speed and endurance, allowing these fish to cover vast distances quickly in search of prey. The pointed nose, tapering body, and powerful tail fin minimize water resistance, enabling them to slice through water with minimal effort. This shape also helps in maintaining stability and balance at high speeds, making these fish formidable hunters in open water.

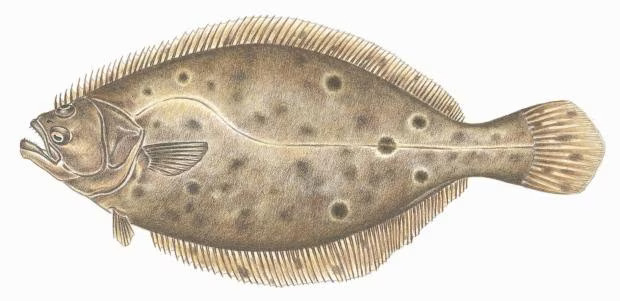

Some game fish, like flounder and halibut, have flattened bodies that allow them to lie close to the seafloor. This shape is an adaptation for a benthic lifestyle, where the fish can easily camouflage themselves against the ocean floor to avoid predators and ambush prey. The flat shape, combined with the ability to change colour to match their surroundings, makes them nearly invisible to both prey and predators. This body shape is particularly effective for species that rely on stealth and surprise in their hunting techniques.

Fish such as bluegill, angelfish, and largemouth bass exhibit a deep, laterally compressed body shape, which means their bodies are tall and thin when viewed from the front. This shape is advantageous in environments with dense vegetation or structures, such as coral reefs or freshwater lakes with abundant aquatic plants. The compressed body allows these fish to make sharp turns and manoeuvre easily among obstacles, making them adept at navigating complex habitats. This agility is crucial for both escaping predators and pursuing prey in confined spaces.

Eel-like game fish, such as the northern pike or barracuda, have long, slender bodies that allow them to strike quickly and with precision. This shape is particularly suited to ambush predators that rely on sudden bursts of speed to capture prey. The elongated body provides the necessary flexibility and range of motion to execute rapid, sideways lunges, often surprising prey with an unexpected attack. Additionally, this shape enables these fish to navigate through narrow crevices and densely packed aquatic vegetation, where they can lie in wait for unsuspecting prey.

Some game fish, like groupers and triggerfish, have a more robust, boxy shape. These fish are typically slower but more powerful, with bodies designed for strength rather than speed. The stout shape is ideal for species that inhabit rocky reefs or areas with strong currents, where manoeuvrability and the ability to withstand pressure are more important than speed. These fish often rely on their strong jaws to crush hard-shelled prey like crabs and molluscs, making their body shape well-suited to their feeding strategy.

The diverse shapes of game fish are a testament to the evolutionary adaptations that have allowed these species to thrive in various aquatic environments. Each shape serves a specific purpose, whether it’s achieving high speeds in open water, navigating complex habitats, or ambushing prey. Understanding these adaptations not only enhances our appreciation of the natural world but also aids anglers in selecting the right strategies and techniques when pursuing different species. Ultimately, the shape of a game fish is a key factor in its success as a predator and its role in the aquatic ecosystem.

How To Treat Fish Poison

Fish poisoning is a serious and sometimes life-threatening condition that occurs after the consumption of toxic fish or seafood. It can manifest in various forms, including ciguatera, scombroid, and tetrodotoxin poisoning, each with distinct symptoms and treatment approaches. Immediate recognition and appropriate management are essential to minimize the health risks associated with fish poisoning.

Types of Fish Poisoning

Ciguatera Poisoning: Ciguatera is the most common form of fish poisoning, caused by eating fish contaminated with toxins produced by dinoflagellates, a type of marine plankton. The toxins accumulate in larger fish such as barracuda, grouper, and snapper. Symptoms of ciguatera poisoning include gastrointestinal issues like nausea, vomiting, and diarrhoea, followed by neurological symptoms such as tingling, numbness, and a reversal of temperature sensation (cold things feel hot and vice versa).

Scombroid Poisoning: Scombroid poisoning results from consuming fish that have not been properly refrigerated, leading to the growth of bacteria that produce histamine. This type of poisoning is often mistaken for an allergic reaction, as it causes symptoms like flushing, hives, itching, and difficulty breathing. Fish commonly associated with scombroid poisoning include tuna, mackerel, and mahi-mahi.

Tetrodotoxin Poisoning: Tetrodotoxin poisoning is most often associated with the consumption of pufferfish, a delicacy in some cultures, especially in Japan. This toxin is extremely potent, and symptoms include numbness, dizziness, nausea, and in severe cases, paralysis and respiratory failure.

The treatment of fish poisoning varies depending on the type and severity of the symptoms. However, there are some general guidelines that can be applied across different types of fish poisoning.

Immediate Medical Attention: The first and most crucial step is to seek immediate medical attention. Fish poisoning can escalate quickly, and professional medical care is essential to manage symptoms and prevent complications. If someone exhibits severe symptoms, such as difficulty breathing, chest pain, or loss of consciousness, call emergency services immediately.

Supportive Care: In cases of ciguatera and scombroid poisoning, treatment is largely supportive. This includes managing symptoms such as dehydration from vomiting and diarrhoea through fluid replacement, and using antihistamines to alleviate itching and rash in scombroid poisoning. In severe cases, patients may require hospitalization for intravenous fluids and medications.

Activated Charcoal: For certain types of fish poisoning, activated charcoal may be administered in the early stages to bind the toxins in the stomach and reduce their absorption into the bloodstream. This is most effective when administered within a few hours of ingestion.

Avoiding Further Exposure: For individuals who have experienced ciguatera poisoning, it is important to avoid consuming fish from the same area, as repeat exposure can lead to more severe symptoms. Awareness of local advisories regarding fish consumption can help prevent such incidents.

Specific Antidotes: In the case of tetrodotoxin poisoning, there is no specific antidote, and treatment is focused on supportive care. However, some studies suggest that certain medications, such as neostigmine, may help alleviate symptoms, though these are not widely used or available.

Prevention is the best strategy when it comes to fish poisoning. This includes being aware of the types of fish that are commonly associated with poisoning, ensuring proper storage and handling of fish, and adhering to local advisories on fish consumption. Additionally, consumers should be cautious when eating fish in areas where fish poisoning is prevalent.

Fish poisoning is a serious condition that requires prompt medical attention and appropriate treatment. By understanding the different types of fish poisoning and their associated symptoms, as well as taking preventive measures, the risks can be minimized, ensuring safer consumption of seafood.

The Role and Impact of Prevailing Winds

Prevailing winds are the dominant winds that blow consistently from a specific direction over a particular region of the Earth’s surface. They are crucial components of the Earth’s climate system, influencing weather patterns, ocean currents, and human activities. Understanding prevailing winds is essential for comprehending global climate dynamics and their impact on various geographical regions.

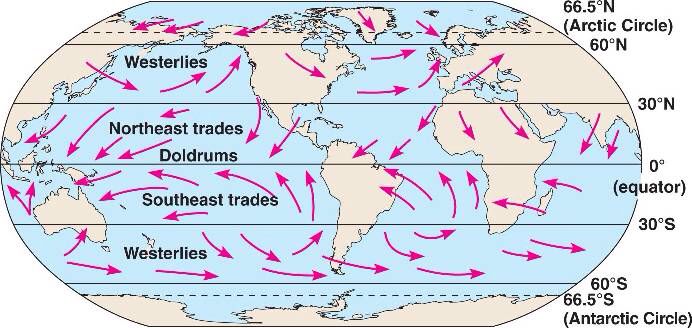

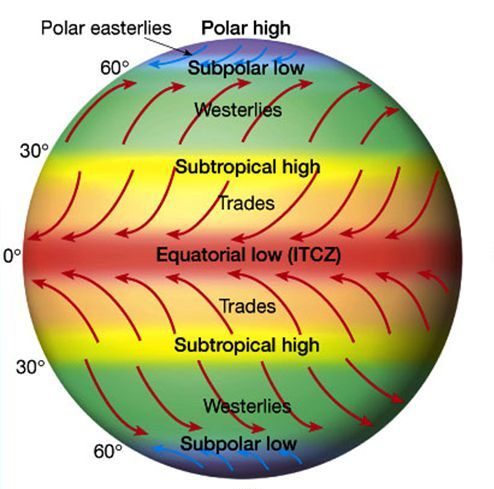

Prevailing winds result from the Earth’s rotation and the unequal heating of the Earth’s surface by the sun. The Coriolis effect, caused by the Earth’s rotation, deflects the direction of these winds, creating distinct wind patterns across the globe. The primary zones of prevailing winds are the trade winds, the westerlies, and the polar easterlies.

Trade Winds: Located between the equator and 30 degrees latitude in both hemispheres, trade winds blow from the northeast in the Northern Hemisphere and from the southeast in the Southern Hemisphere. These winds are driven by the intense solar heating at the equator, causing warm air to rise and move toward the poles, where it cools and descends, creating a circulation pattern known as the Hadley Cell.

Westerlies: Found between 30 and 60 degrees latitude in both hemispheres, the westerlies blow from the west to the east. These winds are formed by the Ferrel Cell, where air moves poleward from the subtropical high-pressure zones and is deflected eastward by the Coriolis effect.

Polar Easterlies: These winds occur between 60 degrees latitude and the poles, blowing from the east to the west. They are the result of cold, dense air descending at the poles and moving toward the lower latitudes, influenced by the Polar Cell.

Prevailing winds play a significant role in determining climate patterns. For instance, the trade winds bring moist air to the equatorial regions, contributing to the heavy rainfall and lush tropical climates. Conversely, the westerlies influence the weather in the mid-latitudes, often bringing storms and precipitation to regions such as North America and Europe. The polar easterlies help maintain the cold temperatures of the polar regions.

Moreover, prevailing winds are crucial in driving ocean currents, which in turn regulate global climate. The trade winds, for example, drive the equatorial currents, while the westerlies are responsible for the major currents in the mid-latitudes, such as the North Atlantic Drift. These ocean currents redistribute heat around the planet, affecting weather patterns and marine ecosystems.

Prevailing winds have historically influenced human activities, particularly in navigation and agriculture. Sailors relied on the predictability of the trade winds and the westerlies for transoceanic voyages during the Age of Exploration. In agriculture, understanding prevailing wind patterns helps farmers anticipate weather conditions and manage crops effectively.

Today, prevailing winds are harnessed for renewable energy through wind turbines. Regions with consistent and strong prevailing winds are ideal for wind farms, contributing to sustainable energy production and reducing reliance on fossil fuels.

Prevailing winds are a fundamental aspect of the Earth’s atmospheric dynamics, shaping climate patterns, driving ocean currents, and influencing human activities. Their consistent and predictable nature makes them a critical factor in both natural processes and human endeavours. As our understanding of these winds deepens, we can better appreciate their role in the Earth’s climate system and utilize this knowledge to address contemporary environmental challenges, such as climate change and sustainable energy development.

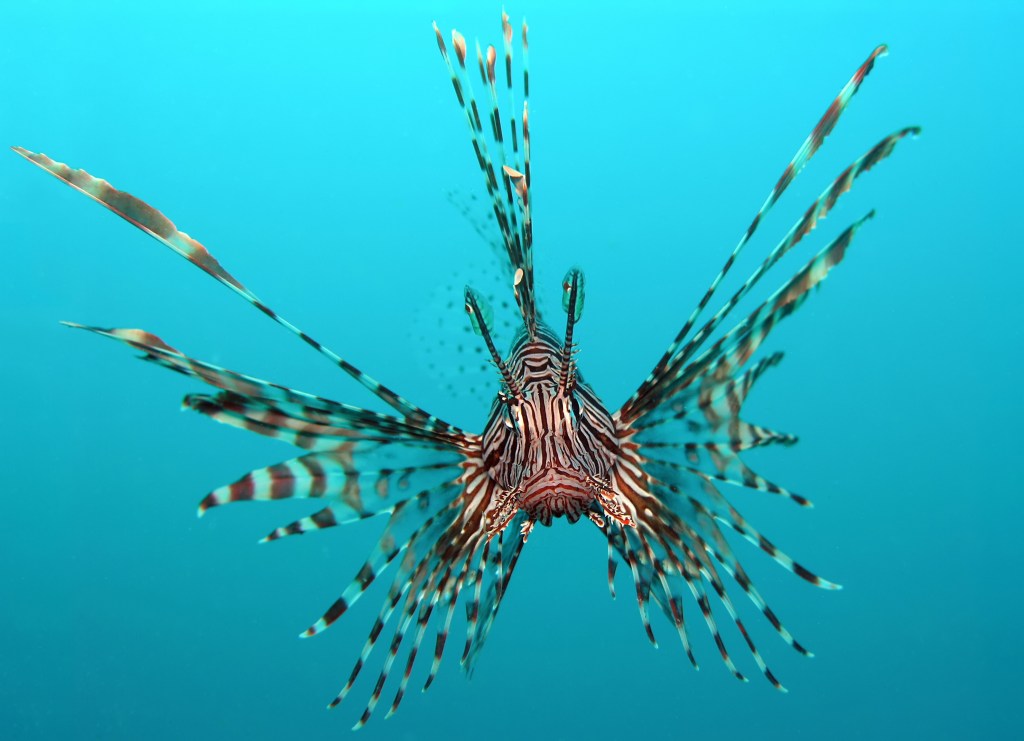

The Invasion of Lionfish: A Marine Ecosystem Crisis

The invasion of lionfish (Pterois volitans and Pterois miles) in the Atlantic Ocean and Caribbean Sea represents one of the most concerning ecological crises of recent times. Native to the Indo-Pacific region, lionfish have become a destructive force in non-native waters, where they pose significant threats to marine biodiversity, fisheries, and coral reef ecosystems.

Lionfish were first documented in the Atlantic Ocean off the coast of Florida in the mid-1980s, likely introduced through the aquarium trade. Their population exploded rapidly due to their high reproductive rate, lack of natural predators, and the favourable conditions of the Atlantic and Caribbean waters. Female lionfish can lay up to 2 million eggs per year, leading to swift and widespread colonization. Their spread has been facilitated by ocean currents, enabling them to inhabit a range extending from North Carolina down to the northern coast of South America and throughout the Caribbean Sea.

The impact of lionfish on local ecosystems is profound and multifaceted. As voracious predators, lionfish consume a wide variety of smaller fish and crustaceans, many of which are vital to the health of coral reefs. Their diet includes juvenile fish of commercially important species, such as grouper and snapper, which has significant implications for local fisheries. By preying on herbivorous fish that keep algae in check, lionfish indirectly contribute to the overgrowth of algae on coral reefs, which can smother corals and reduce biodiversity.

The rapid depletion of native fish populations disrupts the ecological balance and reduces the resilience of coral reef ecosystems. Studies have shown that lionfish can reduce juvenile fish recruitment by up to 79% on invaded reefs. This predatory pressure has cascading effects, altering species composition and undermining the functional integrity of these ecosystems.

Controlling the lionfish invasion has proven to be challenging due to their high reproductive capacity and the vastness of the affected area. Traditional methods such as trapping and spearfishing are employed to reduce their numbers, but these efforts are labour-intensive and localized. Community involvement and incentivized lionfish hunting competitions have been initiated in various regions to increase removal efforts. Additionally, research is being conducted to explore biological control methods, such as the potential use of native predators or parasites.

Public awareness campaigns are crucial in promoting responsible aquarium practices to prevent future introductions of invasive species. Educating the public about the ecological risks associated with releasing non-native species into the wild is a vital step in mitigating similar invasions.

The invasion of lionfish in the Atlantic and Caribbean waters is a stark reminder of the fragility of marine ecosystems and the far-reaching consequences of human activities. The lionfish crisis underscores the importance of preventing the introduction of non-native species and highlights the need for coordinated and sustained management efforts. Addressing this issue requires a combination of scientific research, community engagement, and policy measures to protect and restore affected marine habitats. By learning from this invasion, we can better prepare for and prevent future ecological disruptions, ensuring the health and diversity of our ocean ecosystems.